Pancreatic cancer

| Pancreatic Cancer | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

|

|

| ICD-10 | C25. |

| ICD-9 | 157 |

| OMIM | 260350 |

| DiseasesDB | 9510 |

| MedlinePlus | 000236 |

| eMedicine | med/1712 |

| MeSH | D010190 |

Pancreatic cancer is a malignant neoplasm of the pancreas. By the end of 2010 in the United States, it is estimated about 43,140 individuals will be diagnosed with this condition, and 36,800 will die from the disease.[1] The prognosis is relatively poor, but has improved; the three-year survival rate is now about thirty percent, but fewer than 5 percent of those diagnosed are still alive five years after diagnosis. Complete remission is still rather rare.[2]

About 95% of exocrine pancreatic cancers are adenocarcinomas (M8140/3). The remaining 5% include adenosquamous carcinomas, signet ring cell carcinomas, hepatoid carcinomas, colloid carcinomas, undifferentiated carcinomas, and undifferentiated carcinomas with osteoclast-like giant cells.[3] Exocrine pancreatic tumors are far more common than pancreatic endocrine tumors, which make up about 1% of total cases.[4][5]

Contents |

Signs and symptoms

Presentation

Pancreatic cancer is sometimes called a "silent killer" because early pancreatic cancer often does not cause symptoms,[6] and the later symptoms are usually nonspecific and varied.[6] Therefore, pancreatic cancer is often not diagnosed until it is advanced.[6] Common symptoms include:

- Pain in the upper abdomen that typically radiates to the back[6] (seen in carcinoma of the body or tail of the pancreas)

- Loss of appetite and/or nausea and vomiting[6]

- Significant weight loss

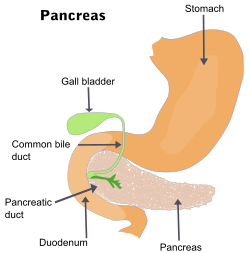

- Painless jaundice (yellow skin/eyes, dark urine)[6] when a cancer of the head of the pancreas (about 60% of cases) obstructs the common bile duct as it runs through the pancreas. This may also cause pale-colored stool and steatorrhea.

- Trousseau sign, in which blood clots form spontaneously in the portal blood vessels, the deep veins of the extremities, or the superficial veins anywhere on the body, is sometimes associated with pancreatic cancer.

- Diabetes mellitus, or elevated blood sugar levels. Many patients with pancreatic cancer develop diabetes months to even years before they are diagnosed with pancreatic cancer, suggesting new onset diabetes in an elderly individual may be an early warning sign of pancreatic cancer.[7]

- Clinical depression has been reported in association with pancreatic cancer, sometimes presenting before the cancer is diagnosed. However, the mechanism for this association is not known.[8]

Causes

Risk factors for pancreatic cancer include:[6][9]

- Age (particularly over 60)[6]

- Male sex (likeliness of up to 30% over females)

- Smoking. Cigarette smoking has a risk ratio of 1.74 with regard to pancreatic cancer; a decade of nonsmoking after heavy smoking is associated with a risk ratio of 1.2.[10]

- Diets low in vegetables and fruits[11]

- Diets high in red meat[12]

- Diets high in sugar-sweetened drinks (soft drinks) risk ratio 1.87[13]. In particular, common soft drink sweetener fructose has been linked to growth of pancreatic cancer cells.[14]

- Obesity[15]

- Diabetes mellitus is both risk factor for pancreatic cancer, and, as noted earlier, new onset diabetes can be an early sign of the disease.

- Chronic pancreatitis has been linked, but is not known to be causal. The risk of pancreatic cancer in individuals with familial pancreatitis is particularly high.

- Helicobacter pylori infection

- Family history, 5–10% of pancreatic cancer patients have a family history of pancreatic cancer. The genes responsible for most of this clustering in families have yet to be identified. Pancreatic cancer has been associated with the following syndromes; autosomal recessive ataxia-telangiectasia and autosomal dominantly inherited mutations in the BRCA2 gene and PALB2 gene, Peutz-Jeghers syndrome due to mutations in the STK11 tumor suppressor gene, hereditary non-polyposis colon cancer (Lynch syndrome), familial adenomatous polyposis, and the familial atypical multiple mole melanoma-pancreatic cancer syndrome (FAMMM-PC) due to mutations in the CDKN2A tumor suppressor gene.[2][16]

- Gingivitis or periodontal disease[17]

Australia and Canada, being members of the International Cancer Genome Consortium, are leading efforts to map pancreatic cancer's complete genome.

Alcohol

It is controversial whether alcohol consumption is a risk factor for pancreatic cancer. Drinking alcohol excessively is a major cause of chronic pancreatitis, which in turn predisposes to pancreatic cancer. However, chronic pancreatitis associated with alcohol consumption does not increase risk of pancreatic cancer as much as other types of chronic pancreatitis.[18] Overall, the association is consistently weak and the majority of studies have found no association.[19][20][21][22]

Some studies suggest a relationship,[23] with risk increasing with increasing amount of alcohol intake.[24][25] Risk is greatest in heavy drinkers[26][27][28] mostly on the order of four or more drinks per day.[29] But there appears to be no increased risk for people consuming up to 30g of alcohol a day,[22][30] so most of the U.S. consumes alcohol at a level that "is probably not a risk factor for pancreatic cancer".[28]

Several studies caution that their findings could be due to confounding factors.[27][31] Even if a link exists, it "could be due to the contents of some alcoholic beverages"[32] other than the alcohol itself. One Dutch study even found that drinkers of white wine had lower risk.[33]

A pooled analysis concluded, "Our findings are consistent with a modest increase in risk of pancreatic cancer with consumption of 30 or more grams of alcohol per day".[34]

Diagnosis

Most patients with pancreatic cancer experience pain, weight loss, or jaundice.[35]

Pain is present in 80 to 85 percent of patients with locally advanced or advanced metastic disease. The pain is usually felt in the upper abdomen as a dull ache that radiates straight through to the back. It may be intermittent and made worse by eating. Weight loss can be profound; it can be associated with anorexia, early satiety, diarrhea, or steatorrhea. Jaundice is often accompanied by pruritus and dark urine. Painful jaundice is present in approximately one-half of patients with locally unresectable disease, while painless jaundice is present in approximately one-half of patients with a potentially resectable and curable lesion.

The initial presentation varies according to location of the cancer. Malignancies in the pancreatic body or tail usually present with pain and weight loss, while those in the head of the gland typically present with steatorrhea, weight loss, and jaundice. The recent onset of atypical diabetes mellitus, a history of recent but unexplained thrombophlebitis (Trousseau sign), or a previous attack of pancreatitis are sometimes noted.

Courvoisier sign defines the presence of jaundice and a painlessly distended gallbladder as strongly indicative of pancreatic cancer, and may be used to distinguish pancreatic cancer from gallstones.

Tiredness, irritability and difficulty eating due to pain also exist. Pancreatic cancer is usually discovered during the course of the evaluation of aforementioned symptoms.

Liver function tests can show a combination of results indicative of bile duct obstruction (raised conjugated bilirubin, γ-glutamyl transpeptidase and alkaline phosphatase levels). CA19-9 (carbohydrate antigen 19.9) is a tumor marker that is frequently elevated in pancreatic cancer. However, it lacks sensitivity and specificity. When a cutoff above 37 U/mL is used, this marker has a sensitivity of 77% and specificity of 87% in discerning benign from malignant disease. CA 19-9 might be normal early in the course, and could be elevated due to benign causes of biliary obstruction.[36]

Imaging studies, such as computed tomography (CT scan) and endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) can be used to identify the location and form of the cancer.

Pathology

_Case_01.jpg)

The definitive diagnosis is made by a percutaneous needle biopsy or surgical excision of the radiologically suspicious tissue. Endoscopic ultrasound is often used to visually guide the needle biopsy procedure.[37]

The most common form of pancreatic cancer (ductal adenocarcinoma) is typically characterized by moderately to poorly differentiated glandular structures on microscopic examination. Pancreatic cancer has an immunohistochemical profile that is similar to hepatobiliary cancers (e.g. cholangiocarcinoma) and some stomach cancers; thus, it may not always be possible to be certain that a tumour found in the pancreas arose from it.

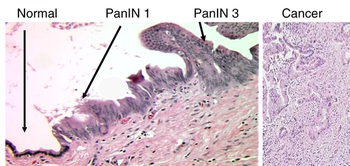

Like colorectal carcinoma, pancreatic carcinoma is thought to arise, typically, from nonmalignant precursor lesions; i.e., it is thought to follow a preneoplasm-neoplasm-carcinoma sequence. In the prototypical colorectal cancer, the lesion has arisen from a tubular adenoma, which developed from colorectal mucosa with an adenomatosis polyposis coli gene mutation. In pancreatic adenocarcinoma, the preneoplastic lesion is pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia 1a (PanIN1a) and pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia 1b (PanIN1b) the neoplastic lesions pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia 2 (PanIN2) and pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia 3 (PanIN3).

Screening

In the September 2009 issue of the journal Cancer Prevention Research, scientists from the University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center identified microRNAs associated with pancreatic cancer from blood samples of pancreatic cancer patients, leading to a new and minimally invasive approach to early detection. Expression of higher levels of miR-155 circulating in blood was identified as a potential early stage biomarker, and expression of miR196a was shown to increase during disease progression. Using a panel of 4 miRNA biomarkers, miR-21, miR-210, miR-155, and miR-196a, the study achieved 64% sensitivity and 89% specificity in a sample of 28 pancreatic cancer patients and 19 healthy controls.[38]

Prevention

According to the American Cancer Society, there are no established guidelines for preventing pancreatic cancer, although cigarette smoking has been reported as responsible for 20–30% of pancreatic cancers.[39]

The ACS recommends keeping a healthy weight, and increasing consumption of fruits, vegetables, and whole grains, while decreasing red meat intake, although there is no consistent evidence this will prevent or reduce pancreatic cancer specifically.[40][41] In 2006, a large prospective cohort study of over 80,000 subjects failed to prove a definite association.[42] The evidence in support of this lies mostly in small case-control studies.[11]

In September 2006, a long-term study concluded taking vitamin D can substantially reduce the risk of pancreatic cancer (as well as other cancers) by up to 50%, but this study needs to evaluate fully the risks, costs and potential benefits of taking vitamin D.[43][44][45]

Several studies, including one published on 1 June 2007, indicate B vitamins, such as B12, B6, and folate, can reduce the risk of pancreatic cancer when consumed in food, but not when ingested in vitamin tablet form.[46][47]

Treatment

Surgery

Treatment of pancreatic cancer depends on the stage of the cancer.[48] The Whipple procedure is the most common surgical treatment for cancers involving the head of the pancreas. This procedure involves removing the pancreatic head and the curve of the duodenum together (pancreato-duodenectomy), making a bypass for food from stomach to jejunum (gastro-jejunostomy) and attaching a loop of jejunum to the cystic duct to drain bile (cholecysto-jejunostomy). It can only be performed if the patient is likely to survive major surgery and if the cancer is localized without invading local structures or metastasizing. It can, therefore, only be performed in the minority of cases.

Cancers of the tail of the pancreas can be resected using a procedure known as a distal pancreatectomy.[48] Recently, localized cancers of the pancreas have been resected using minimally invasive (laparoscopic) approaches.[49]

After surgery, adjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine has been shown in several large randomized studies to significantly increase the 5-year survival (from approximately 10 to 20%), and should be offered if the patient is fit after surgery (Oettle et al. JAMA 2007, Neoptolemos et al. NEJM 2004, Oettle et al. ASCO proc 2007). There is a study being done currently by Washington University using interferon to treat the cancer, and it has boosted survival times somewhat further. Addition of radiation therapy is a hotly debated topic, with groups in the US often favoring the use of adjuvant radiation therapy, while groups in Europe do not, due to the lack of any large randomized studies to show any survival benefit of this strategy.[50]

Surgery can be performed for palliation, if the malignancy is invading or compressing the duodenum or colon. In that case, bypass surgery might overcome the obstruction and improve quality of life, but it is not intended as a cure.[37]

Chemotherapy

In patients not suitable for resection with curative intent, palliative chemotherapy may be used to improve quality of life and gain a modest survival benefit. Gemcitabine was approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration in 1998, after a clinical trial reported improvements in quality of life and a 5-week improvement in median survival duration in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. This marked the first FDA approval of a chemotherapy drug primarily for a nonsurvival clinical trial endpoint. Gemcitabine is administered intravenously on a weekly basis. Addition of oxaliplatin (Gem/Ox) conferred benefit in small trials, but is not yet standard therapy.[51] A recently published study, ECOG 6201, failed to show superiority of GEMOX over gemcitabine alone (Poplin et al., JCO 2009, Louvet et al. JCO 2005). Fluorouracil (5FU) may also be included; however, no large randomized study has shown significant survival benefit from this addition (Berlin et al. JCO 2002). One so far unpublished trial has shown a trend (p=0.08) towards a significant benefit from adding capecitabine to gemcitabine (Cunningham et al. JCO 2009). Meta-analysis has, however, shown benefit from combination therapy, especially in fit (PS 0-1) patients (Sultana et al. BJC 2009, Cunningham et al. JCO 2009).

On the basis of a Canadian-led Phase III randomised controlled trial involving 569 patients with advanced pancreatic cancer, the US FDA has licensed the use of erlotinib (Tarceva) in combination with gemcitabine as a palliative regimen for pancreatic cancer. This trial compared the action of gemcitabine/erlotinib to gemcitabine/placebo, and demonstrated improved survival rates, improved tumor response and improved progression-free survival rates (Moore et al. JCO 2005). The survival improvement with the combination is on the order of less than four weeks, leading some cancer experts to question the incremental value of adding erlotinib to gemcitabine treatment. New trials are now investigating the effect of the above combination in the adjuvant and neoadjuvant setting.[52] A trial of antiangiogenesis agent bevacizumab (Avastin) as an addition to chemotherapy has shown no improvement in survival of patients with advanced pancreatic cancer (Kindler et al.). It may cause higher rates of high blood pressure, bleeding in the stomach and intestines, and intestinal perforations.

Prognosis

Patients diagnosed with pancreatic cancer typically have a poor prognosis, partly because the cancer usually causes no symptoms early on, leading to locally advanced or metastatic disease at time of diagnosis. Median survival from diagnosis is around 3 to 6 months; 5-year survival is less than 5%.[53] With 37,170 cases diagnosed in the United States in 2007, and 33,700 deaths, pancreatic cancer has one of the highest fatality rates of all cancers, and is the fourth-highest cancer killer in the United States among both men and women. Although it accounts for only 2.5% of new cases, pancreatic cancer is responsible for 6% of cancer deaths each year.[54]

Pancreatic cancer may occasionally result in diabetes. Insulin production is hampered, and it has been suggested the cancer can also prompt the onset of diabetes and vice versa.[55] Thus, diabetes is both a risk factor for the development of pancreatic cancer and an early sign of the disease in the elderly.

Epidemiology

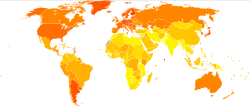

no data <1 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 >10

See also

- Category:Deaths from pancreatic cancer

- Category:Pancreatic cancer survivors

- Gastrointestinal cancer

References

- ↑ "Pancreatic Cancer — National Cancer Institute, U.S. National Institutes of Health (Accessed 10 May 2009)". Cancer.gov. http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/types/pancreatic. Retrieved 2009-09-15.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Ghaneh P, Costello E, Neoptolemos JP (August 2007). "Biology and management of pancreatic cancer". Gut 56 (8): 1134–52. doi:10.1136/gut.2006.103333. PMID 17625148.

- ↑ "Types of Tumors". Johns Hopkins University. http://pathology.jhu.edu/pancreas/BasicTypes1.php. Retrieved Date.

- ↑ Yao JC, Eisner MP, Leary C, et al. (December 2007). "Population-based study of islet cell carcinoma". Annals of Surgical Oncology 14 (12): 3492–500. doi:10.1245/s10434-007-9566-6. PMID 17896148.

- ↑ "Endocrine Neoplasms". http://pathology.jhu.edu/pancreas/TreatmentEndocrine.php.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 6.7 "What You Need To Know About Cancer of the Pancreas — National Cancer Institute". 2002-09-16. p. 4/5. http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/wyntk/pancreas/page4. Retrieved 2007-12-22.

- ↑ Pannala R, Basu A, Petersen GM, Chari ST (January 2009). "New-onset diabetes: a potential clue to the early diagnosis of pancreatic cancer". The Lancet Oncology 10 (1): 88–95. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70337-1. PMID 19111249.

- ↑ Carney CP, Jones L, Woolson RF, Noyes R, Doebbeling BN (2003). "Relationship between depression and pancreatic cancer in the general population". Psychosomatic Medicine 65 (5): 884–8. doi:10.1097/01.PSY.0000088588.23348.D5. PMID 14508036.

- ↑ "ACS :: What Are the Risk Factors for Cancer of the Pancreas?". http://www.cancer.org/docroot/CRI/content/CRI_2_4_2X_What_are_the_risk_factors_for_pancreatic_cancer_34.asp?sitearea=. Retrieved 2007-12-13.

- ↑ Iodice S, Gandini S, Maisonneuve P, Lowenfels AB (July 2008). "Tobacco and the risk of pancreatic cancer: a review and meta-analysis". Langenbeck's Archives of Surgery 393 (4): 535–45. doi:10.1007/s00423-007-0266-2. PMID 18193270.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Chan JM, Wang F, Holly EA (September 2005). "Vegetable and fruit intake and pancreatic cancer in a population-based case-control study in the San Francisco bay area". Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention 14 (9): 2093–7. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0226. PMID 16172215.

- ↑ "Red Meat May Be Linked to Pancreatic Cancer". Journal of the National Cancer Institute. WebMD. 2005-10-05. http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/514268. Retrieved 2008-03-05.

- ↑ "Soft Drink and Juice Consumption and Risk of Pancreatic Cancer: The Singapore Chinese Health Study". http://cebp.aacrjournals.org/content/19/2/447.short.

- ↑ "Cancer cells slurp up fructose, U.S. study says". Reuters. 2010-08-02. http://www.healthzone.ca/health/newsfeatures/article/843084--cancer-cells-slurp-up-fructose-u-s-study-finds?bn=1. Retrieved 2010-08-02.

- ↑ "Obesity Linked to Pancreatic Cancer". American Cancer Society. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention (Vol. 14, No. 2: 459–466). 2005-03-06. http://www.cancer.org/docroot/NWS/content/NWS_1_1x_Obesity_Linked_to_Pancreatic_Cancer.asp. Retrieved 2008-03-05.

- ↑ Efthimiou E, Crnogorac-Jurcevic T, Lemoine NR, Brentnall TA (February 2001). "Inherited predisposition to pancreatic cancer". Gut 48 (2): 143–7. doi:10.1136/gut.48.2.143. PMID 11156628.

- ↑ Michaud DS, Joshipura K, Giovannucci E, Fuchs CS (January 2007). "A prospective study of periodontal disease and pancreatic cancer in US male health professionals". Journal of the National Cancer Institute 99 (2): 171–5. doi:10.1093/jnci/djk021. PMID 17228001.

- ↑ Cancer Research UK Pancreatic cancer risks and causes

- ↑ National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Alcohol and Cancer - Alcohol Alert No. 21-1993

- ↑ American Cancer Society Coffee and Alcohol Do Not Pose a Risk for Pancreatic Cancer

- ↑ Villeneuve PJ, Johnson KC, Hanley AJ, Mao Y (February 2000). "Alcohol, tobacco and coffee consumption and the risk of pancreatic cancer: results from the Canadian Enhanced Surveillance System case-control project. Canadian Cancer Registries Epidemiology Research Group". European Journal of Cancer Prevention 9 (1): 49–58. doi:10.1097/00008469-200002000-00007. PMID 10777010.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Michaud DS, Giovannucci E, Willett WC, Colditz GA, Fuchs CS (May 2001). "Coffee and alcohol consumption and the risk of pancreatic cancer in two prospective United States cohorts". Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention 10 (5): 429–37. PMID 11352851. http://cebp.aacrjournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=11352851.

- ↑ Ahlgren JD (April 1996). "Epidemiology and risk factors in pancreatic cancer". Seminars in Oncology 23 (2): 241–50. PMID 8623060.

- ↑ Cuzick J, Babiker AG (March 1989). "Pancreatic cancer, alcohol, diabetes mellitus and gall-bladder disease". International Journal of Cancer 43 (3): 415–21. doi:10.1002/ijc.2910430312. PMID 2925272.

- ↑ Harnack LJ, Anderson KE, Zheng W, Folsom AR, Sellers TA, Kushi LH (December 1997). "Smoking, alcohol, coffee, and tea intake and incidence of cancer of the exocrine pancreas: the Iowa Women's Health Study". Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention 6 (12): 1081–6. PMID 9419407. http://cebp.aacrjournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=9419407.

- ↑ Schottenfeld, D. and J. Fraumeni, ed. Cancer epidemiology and prevention. 2nd ed., ed. Vol. 1996, Oxford University Press: Oxford

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Ye W, Lagergren J, Weiderpass E, Nyrén O, Adami HO, Ekbom A (August 2002). "Alcohol abuse and the risk of pancreatic cancer". Gut 51 (2): 236–9. doi:10.1136/gut.51.2.236. PMID 12117886.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Silverman DT, Brown LM, Hoover RN, et al. (November 1995). "Alcohol and pancreatic cancer in blacks and whites in the United States". Cancer Research 55 (21): 4899–905. PMID 7585527. http://cancerres.aacrjournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=7585527.

- ↑ Olsen GW, Mandel JS, Gibson RW, Wattenberg LW, Schuman LM (August 1989). "A case-control study of pancreatic cancer and cigarettes, alcohol, coffee and diet". American Journal of Public Health 79 (8): 1016–9. doi:10.2105/AJPH.79.8.1016. PMID 2751016.

- ↑ "Pancreatic cancer risk factors". Info.cancerresearchuk.org. 2008-11-04. http://info.cancerresearchuk.org/cancerstats/types/pancreas/riskfactors/. Retrieved 2009-09-15.

- ↑ Zatonski WA, Boyle P, Przewozniak K, Maisonneuve P, Drosik K, Walker AM (February 1993). "Cigarette smoking, alcohol, tea and coffee consumption and pancreas cancer risk: a case-control study from Opole, Poland". International Journal of Cancer 53 (4): 601–7. doi:10.1002/ijc.2910530413. PMID 8436433.

- ↑ Durbec JP, Chevillotte G, Bidart JM, Berthezene P, Sarles H (April 1983). "Diet, alcohol, tobacco and risk of cancer of the pancreas: a case-control study". British Journal of Cancer 47 (4): 463–70. PMID 6849792.

- ↑ Bueno de Mesquita HB, Maisonneuve P, Moerman CJ, Runia S, Boyle P (February 1992). "Lifetime consumption of alcoholic beverages, tea and coffee and exocrine carcinoma of the pancreas: a population-based case-control study in The Netherlands". International Journal of Cancer 50 (4): 514–22. doi:10.1002/ijc.2910500403. PMID 1537615.

- ↑ Genkinger JM, Spiegelman D, Anderson KE, et al. (March 2009). "Alcohol intake and pancreatic cancer risk: a pooled analysis of fourteen cohort studies". Cancer Epidemiology, Biomark ers & Prevention 18 (3): 765–76. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0880. PMID 19258474.

- ↑ Bakkevold KE, Arnesjø B, Kambestad B (April 1992). "Carcinoma of the pancreas and papilla of Vater: presenting symptoms, signs, and diagnosis related to stage and tumour site. A prospective multicentre trial in 472 patients. Norwegian Pancreatic Cancer Trial". Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology 27 (4): 317–25. doi:10.3109/00365529209000081. PMID 1589710.

- ↑ Frank J. Domino M.D.etc. (2007). 5 minutes clinical suite version 3. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Philip Agop, "Pancreatic Cancer". ACP PIER & AHFX DI Essentials. American College of Physicians. 4 Apr 2008. Accessed 7 Apr 2009.

- ↑ OncoGenetics.Org (September 2009). "MicroRNAs circulating in blood show promise as biomarkers to detect pancreatic cancer". OncoGenetics.Org. http://www.oncogenetics.org/web/MicroRNAs-circulating-in-blood-show-promise-as-biomarkers-to-detect-pancreatic-cancer. Retrieved 2009-09-04.

- ↑ "Can Cancer of the Pancreas Be Prevented?". American Cancer Society. http://www.cancer.org/docroot/CRI/content/CRI_2_4_2X_Can_pancreatic_cancer_be_prevented_34.asp?rnav=cri. Retrieved 2007-12-13.

- ↑ Coughlin SS, Calle EE, Patel AV, Thun MJ (December 2000). "Predictors of pancreatic cancer mortality among a large cohort of United States adults". Cancer Causes & Control 11 (10): 915–23. doi:10.1023/A:1026580131793. ISSN 0957-5243. PMID 11142526.

- ↑ Zheng W, McLaughlin JK, Gridley G, et al. (September 1993). "A cohort study of smoking, alcohol consumption, and dietary factors for pancreatic cancer (United States)". Cancer Causes & Control 4 (5): 477–82. doi:10.1007/BF00050867. PMID 8218880.

- ↑ Larsson SC, Håkansson N, Näslund I, Bergkvist L, Wolk A (February 2006). "Fruit and vegetable consumption in relation to pancreatic cancer risk: a prospective study". Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention 15 (2): 301–5. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0696. PMID 16492919.

- ↑ "Health | Vitamin D 'slashes cancer risk'". BBC News. 2006-09-15. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/health/5334534.stm. Retrieved 2009-09-15.

- ↑ "Vitamin D May Cut Pancreatic Cancer". Webmd.com. 2006-09-12. http://www.webmd.com/content/article/127/116673.htm. Retrieved 2009-09-15.

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ {Schernhammer E, Wolpin B, Rifai N, et al. (June 2007). "Plasma folate, vitamin B6, vitamin B12, and homocysteine and pancreatic cancer risk in four large cohorts". Cancer Research 67 (11): 5553–60. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4463. PMID 17545639.

- ↑ United Press International (2 June 2007). "Pancreatic cancer risk cut by B6, B12". http://www.upi.com/Consumer_Health_Daily/Briefing/2007/06/01/pancreatic_cancer_risk_cut_by_b6_b12/3712/. Retrieved 5 September 2009.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 "Surgical Treatment of Pancreatic Cancer". Johns Hopkins University. http://pathology.jhu.edu/pancreas/TreatmentSurgery.php. Retrieved 5 September 2009.

- ↑ "Laparoscopic Pancreas Surgery". Johns Hopkins University. http://pathology.jhu.edu/pancreas/TreatmentLaparoscopic.php. Retrieved 5 September 2009.

- ↑ Neoptolemos JP, Stocken DD, Friess H, et al. (March 2004). "A randomized trial of chemoradiotherapy and chemotherapy after resection of pancreatic cancer". The New England Journal of Medicine 350 (12): 1200–10. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa032295. PMID 15028824.

- ↑ Demols A, Peeters M, Polus M, et al. (February 2006). "Gemcitabine and oxaliplatin (GEMOX) in gemcitabine refractory advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a phase II study". British Journal of Cancer 94 (4): 481–5. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6602966. PMID 16434988.

- ↑ "FDA approval briefing". http://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/AC/05/briefing/2005-4174B1_03_01-OSI-Tarceva.pdf#search=%22%20fda%20erlotinib%20pancreatic%22. Retrieved 2009-09-15.

- ↑ "WHO | Cancer". Who.int. http://www.who.int/tobacco/research/cancer/en/. Retrieved 2009-09-15.

- ↑ Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Murray T, Xu J, Thun MJ (2007). "Cancer statistics, 2007". CA 57 (1): 43–66. doi:10.3322/canjclin.57.1.43. PMID 17237035.

- ↑ Wang F, Herrington M, Larsson J, Permert J (January 2003). "The relationship between diabetes and pancreatic cancer". Molecular Cancer 2: 4. doi:10.1186/1476-4598-2-4. PMID 12556242.

- ↑ "WHO Disease and injury country estimates". World Health Organization. 2009. http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/estimates_country/en/index.html. Retrieved Nov. 11, 2009.

External links

- Pancreatic Cancer at American Cancer Society

- The Johns Hopkins Pancreatic Cancer Web Site

- Pancreatic Cancer Action (UK)

- Pancreatic Cancer Action Network (PanCAN)

- Pancreatic Cancer Canada

- The Pancreatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland

- The Johns Hopkins Pancreatic Cancer Web Site Discussion Board

- Rare Pancreatic & Neuroendocrine Cancer Support

- Pancreatic Cancer UK

- Confronting Pancreatic Cancer (Pancreatica.org)

- Cancer of the Pancreas (Cancer Supportive Care Program)

- The National Familial Pancreas Tumor Registry

- Pancreatic Cancer Collaborative Registry (PCCR)

- The Lustgarten Foundation For Pancreatic Cancer Research

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||